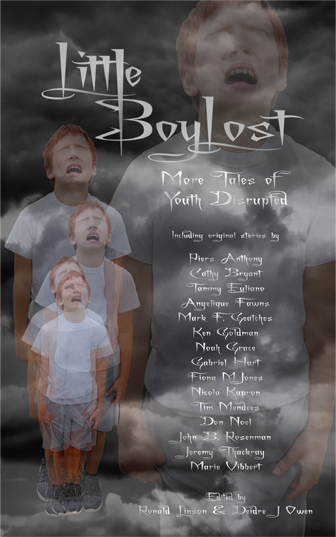

Published in the Mannison Press anthology “Little Boy Lost: More Tales of Youth Disrupted” in February 2020

He heard the snow turn to freezing rain at four o’clock, rattling against the window, but decided to doze a little longer, not wanting to waken the girl on the other side of the driveway. Her bedroom, like his, overlooked the drive, and she opened her window four or five inches for fresh air even on a snowy January night. So despite Papa’s advice, he rolled over for another forty winks.

“This machine will blow away six or eight inches of dry fluffy snow in half  an hour,” Papa said yesterday afternoon as he went over with Shy Boy how to operate the snow blower. “But snow that’s been sleeted or rained on for an hour or two gets heavy, and that will be a different story.” So he’d agreed to set an alarm for five a.m., but get up earlier if he heard the weather change the way the forecaster predicted.

an hour,” Papa said yesterday afternoon as he went over with Shy Boy how to operate the snow blower. “But snow that’s been sleeted or rained on for an hour or two gets heavy, and that will be a different story.” So he’d agreed to set an alarm for five a.m., but get up earlier if he heard the weather change the way the forecaster predicted.

Mama hadn’t been sure he should run the snowblower all by himself. State law, she reminded Papa at dinner, said people younger than eighteen couldn’t be employed to run power equipment. “If you pay him forty dollars to have the driveway and sidewalk clear by the time you get up in the morning, aren’t you employing him?”

“Grace,” Papa said, “that’s ridiculous. This is just taking on more household chores to earn a bigger allowance.”

“And I’ve used the snowblower with Papa lots of times,” Shy Boy added. He liked the idea of earning several hundred dollars this winter, although he didn’t know how he might spend it. “It’s not hard. Besides, I’ll be eighteen in April. And I’m plenty strong enough.”

“You can say that again,” Papa said. “Anyone who can bench-press three hundred pounds is a lot more fit than I am.” Then he added the clincher: “Do you want me to have a heart attack, Grace, while Harold lingers in bed?”

Papa always called him by his real name; only Mama still called him Shy Boy, and only when there was no one else around. Papa liked to pretend the nickname was because he was strong as a horse, like the famous mustang who shied away from most cowboys but was tamed on television by a horse whisperer. They all knew, though, that he was not confident around people. “Introverted,” the school psychologist had said when Mama took him in first grade. She preferred to say “reserved.”

The fact was he didn’t have many friends. He chose weightlifting not only because he was muscular but because it was the high school team sport he could manage with the least interaction.

If he was diffident with boys, he was downright timid with girls. Like the girl across the driveway. Maria. She was almost eighteen, too. He knew her name from school, but had never spoken to her except to say “good morning” at the bus stop, and even that made him blush.

But he was in love with her, in a storybook way. Although she drew her bedroom window shade at night, he could tell from the bluish light when she was at her computer, and imagined sending her a text message or a tweet or one of those things he knew nothing about. He arranged the furniture in his room so he could lie in bed reading and see her window, and he never opened his own window and pulled down the shade until she turned her lights out and went to sleep.

Occasionally she got ready for bed with a light somewhere, probably a closet light, that cast her shadow on the blind. In geography class they had learned about an Indonesian theater with shadow puppets, and when he could see her shadow undressing and putting on a nightgown he thought of it as his private wayang theater. He was glad to be alone at those moments, because it aroused him in a way that he enjoyed. He was sure he would go limp with embarrassment if she ever pulled up the blind and looked across to see him staring, even if she were entirely naked.

When the alarm woke him at five he heard hard sleet or freezing rain. He knew it had been a mistake not to get up right away when the weather changed, even if that had meant waking Maria up. He dressed quickly, and put on his galoshes and the heavy wool cap Mama knit him and his nylon snow jacket that was supposed to be water repellent, and went out to the garage.

The machine started right away, and he let it warm up for a minute before putting it in gear and starting to clear the area in front of the garage, thinking to postpone as long as possible the moment when he would be under her window, when she would pull up the blind to see what the racket was about, and slam the window shut to try to go back to sleep. She always slept until six-thirty.

Papa was right: The moment had long passed when he might have sent a glistening arc of fluffy snow to the sides of the driveway. It was more like the way soft ice cream is squeezed from the machine at the Dairy Queen, and if he slacked off on the hand throttle for even a moment the sodden snow would stop being expelled and plug up the chute.

When that happened, he did as Papa had taught him: Turned the machine off while he poked a hand into the chute to clear the blockage. “Never leave the engine running,” Papa said. “The blades may jammed, but if you get the snow plug cleared they might start spinning again, and you don’t want your hand in there when that happens.”

He only had to stop and re-start a few times while he was clearing the snow in the back yard. But the snow had drifted before it turned to rain, the wind skimming snow off the open stretches behind the house and depositing it in deeper drifts beside the house. He had to stop every few minutes to clear the chute. The closer he got to Maria’s window, the deeper it seemed to get.

By then he was getting cold. His jacket wasn’t as rainproof as he’d thought, so his shoulders were wet. So was Mama’s wool cap. His right hand was numb, because he couldn’t clear the snow out of the chute without taking his glove off.

When it plugged up exactly under her window, he looked up. He had wakened her, as he’d feared. She was standing in the dark window, wearing something. In the light of the streetlight that reflected off the snow, it looked frilly. She waved to him, her hand back and forth as though she were wiping the window, her face close to the window so he could see her smile.

He waved back. Stood there for a moment, grinning like an idiot, and gave her a big overhead wave. Then he took the glove off that hand and bent over to clear the plugged chute. But he forgot to turn off the engine first. It sputtered, the blades not turning.

He put his hand into the chute and began clawing out the packed slush, which went deeper into the throat of the chute than ever before. He reached in again and again, dragging the snow out with his frozen hand.

Suddenly, just as Papa had warned, the blades began turning. Before he could draw back, a blade hit his fingers. Maybe two blades. The hand was so cold and numb that he couldn’t tell how badly he was hurt, but the hand spurted blood on the snow as he wrenched it out of the chute. He had the presence of mind to reach up with his left hand and turn the engine off.

“Oh, you’re hurt!” Maria had opened her window wide. “Wait there! Pack it with snow until I get there!”

He was stupefied. He knew he ought to get the snowblower back in the garage, but knew he couldn’t pull the starter cord with his damaged hand. He tried dragging it back with his left hand, but it was hard to move without the motor running. He looked down to see that his hand was still bleeding, so he did as Maria said and thrust it into a deep snow drift. He could no longer feel the cold.

She was out in no time at all, wearing a thick quilted bathrobe, hurrying through the snowdrifts from her front door in zip-up, fur lined boots that weren’t quite high enough, a roll of gauze and a rolled-up Ace bandage in her gloveless hands. “Oh, Harold, I’m so sorry. I distracted you.”

“It wasn’t your fault, you know. My own stupidity. I should have turned the motor off.”

“Never mind. I’ve just finished a first aid course. I want to be a nurse. Hold out your hand.”

He did. She took it in hers, and deftly wound the gauze around his fingers, and then the stretchy Ace bandage. “It doesn’t feel to me as though you broke anything,” she said. “Does it to you?”

“I can’t tell. It’s so frozen.”

“You should definitely have it X-rayed, and it may need a few stitches. We should get you to the emergency room.”

“I don’t know. Maybe I can just rest it. We can’t get the car out of the driveway yet.”

“Nonsense,” she said. “Let’s go in and wake up your parents.”

He obediently followed her to the back door. It was unlocked, but she ding-donged the doorbell several times, and then opened the door for him. By the time they got in the kitchen, Mama had sensed the urgency and was in the kitchen in her bathrobe.

“Oh, my!” she said.

“Mrs. Garnett, I’m Maria from next door. Harold hurt his hand in the snowblower. I’ve stopped the bleeding, but he ought to get to the emergency room. I’m not even a nurse yet.”

“Thank you, Maria. I’ll get his Papa up and we’ll take him.”

“You can’t, Mama,” he said. “I didn’t finish the driveway. There are big drifts.”

“An ambulance,” Maria said. “Call 9-1-1, and when it comes he can walk out through the snow.”

“You’re right. I’ll telephone,” Mama said. “Thank you for your help.”

“Not to mention. It was my fault. I looked out the window when I heard the snowblower, and distracted him.”

“Never mind. You’d better get back home. You’re not very warmly dressed.”

“Thank you. I’ll wait until the ambulance comes.”

So Mama let her stay, and dialed 9-1-1, and called upstairs to waken Papa. Maria helped Mama get his soaking wet jacket off over the bandaged hand, and put on a dry jacket. By that time Papa had come down and sized the situation up.

“You go upstairs and get dressed, Grace. Hurry, now. You should go with him in the ambulance. I’ll finish the driveway and come to get you when I can get the car out.”

“I’m sorry, Papa. I hurt my hand dragging snow out of the chute.”

“You didn’t turn the motor off like I told you.”

“I had been, Papa, every time it jammed. But . . . “

“I distracted him, Mr. Garnett,” Maria said. “I looked out the window and waved.”

They heard the wail of the ambulance. Mama came back into the kitchen, wearing her coat and snow boots. Papa and Mama and Maria escorted him down the driveway. The EMTs made him lie down in the back, and let Mama sit back there with him.

“Girl,” she said before the door closed. “You get yourself in the house and take a hot shower. You don’t want to catch cold. And thank you.”

“I’ll be all right. I’m not too cold yet. See you later, Harold.”

“Thank you for all your help,” he said. “I’m sorry to drag you out into the cold.” He smiled at her. “Go get inside before you take a chill. I’ll be all right. I’ll see you later.”

It was more words than he’d ever spoken to a girl, and he didn’t feel in the least embarrassed or timid or insecure or reserved.

It was the nicest accident he’d ever had.

-End-