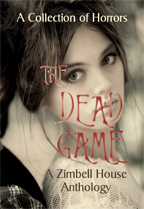

Published in the Zimbell House anthology “Dead Game: A Collection of Horrors” in May 2020

Howard knew that the end was near. Game over. Had he not been so tired, he would have been angry. He hadn’t known until too late what kind of a rigged game Charles had devised.

Or had it been Charles and Meg?

His friend and his wife had been together in the pilot boat; had several times handed him nourishment over the transom, encouragement and fortification to help him – it seemed – complete his swim across The Channel, to be followed the next day by Charles’ effort to better his time and win.

nourishment over the transom, encouragement and fortification to help him – it seemed – complete his swim across The Channel, to be followed the next day by Charles’ effort to better his time and win.

Yet now, not long after the last such replenishing pause — in the very few minutes, Howard thought, that he’d been face-down in the water trying to restore a modicum of momentum in his swimming — the boat was gone. Vanished.

He paused, trying to tread water; it seemed he had no buoyancy left. He willed himself to make a slow, painful aquatic pirouette. There was indeed no sign of the boat. He couldn’t see the white cliffs anymore, either. They must have led him west, where The Channel widens. So he must be still miles from any French beach.

It didn’t matter. The effort simply to turn 360 degrees, trying to keep his head up in order to survey the horizon, had exhausted him. He wasn’t sure he could reach land even if he could see it.

No, in fact, was sure he could not. Unconsciousness, his brain tried to remember, occurs when the core body temperature reaches – was it 86 degrees? Whatever the number, he was cold. Almost numb. But muscles, he and Charles learned years ago, can work for a short period beyond the point at which the brain is too cold to maintain command.

Howard tried to remember how long he had been swimming. They had told him, the last time they gave him a nourishment drink. Had it been eight hours, then? How long ago was that? His brain . . . seemed not . . . to be focused . . . .

The muscles, though . . . were still working. . . .Then . . . the legs . . . could not . . . kick. . . . The . . . arms . . . could not . . ..move . . .

* * *

Charles’ visit this week had been unexpected, a total pleasure. The first evening, they tried to calculate: Had it really been two decades? Good old Chuck, except that he was Charles now, the French way, Shaarlls. And he himself was no longer the American expatriate Howie, but a very British, proper Howard.

They had not come to England together. He had been first, a Rhodes scholar who had matriculated at Harvard after a childhood of constant swimming in the Finger Lakes of upstate New York, and an adolescence in Boston. In his first few months at Oxford he had met dear Meg. Within the year they married, and he stayed. Meg extended her studies of Asian religions. He pursued new fields of inquiry into Chaucer and medieval literature; he soon became a lecturer, a don, an adopted Brit.

So he was there when Chuck arrived, six years younger, full of Dallas piss and vinegar, having accepted his Rhodes as a stepping-stone to where he really wanted to be, Paris, studying Renaissance art. In his first month he met the charming and beautiful Lisette, who had been accepted at Oxford to study Nordic folklore. Before autumn was over he was totally smitten.

Chuck accompanied her home to Vitry-sur-Seine for the holidays, and brought her back to London as his bride, having in those few weeks become Charles, Shaarlls, as he would be the rest of his life.

Charles and Lisette stayed in England for several years, and the couples became as close as four people could possibly be. Looking back years later, Howard thought they were not so much brothers and sisters as companion lovers who might have swapped partners but never did.

For three years they played together: picnicked and saw endless Shakespearean plays at Stratford-on-Avon; hiked the Cotswolds, stopping early each afternoon to enjoy the hospitalities and pleasures of one inn after another; rented houseboats to explore the Forth and Clyde and Union Canals. Both men came from enough money that their lives could always have time for holidays.

And, after a time, they made a game of swimming the English Channel: a contest, the loser to pay for a weekend in Paris.

They would not race in the usual sense, both in the water swimming at once, as in the collegiate competitions at which both had excelled. No, because the English Channel is a 21-mile marathon even if one manages to stay on the shortest route from Shakespeare’s Cliff near Dover to Cap Gris-Nez (the name of that destination a joke because after so long a swim in cold water, only 65 degrees at the end of the summer, one’s nose would inevitably be more blue than gray).

And no, not both at once because an already-formidable swim can be even longer and more exhausting if one is carried by sometimes-formidable tides out to the west where the Channel doubles and finally more than triples in width. They would need each other, and both wives, in a pilot boat to be sure they stayed in that narrowest neck and were not swept away, to say nothing of keeping watch to avoid ships that might not notice swimming specks.

So it was decided: The rules of their game would be to take turns, each timing the other, swimming the same course — on successive days, unless weather or tides might handicap the one who went second.

It was not a game to be taken lightly: First, although both had been medalists in 1,500-meter freestyle competitions, they had to learn an essentially new skill, distances and durations they had never tried. They began practicing with shorter swims that were still two or three times longer than either had experienced, and soon grew far beyond that.

Reading and quizzing others who had done it, they learned to prime their bodies with grease. Not just any oily lubricant, but the traditional English choice of goose fat — not as insulation against the cold, although that was a helpful extra, but to keep the skin from painful chafing in the endless reiteration of a narrow range of motion of shoulders and arms and cupped hands, hips and legs and fluttering feet.

They learned to bulk up with carbs and protein-rich food like eggs before the game, because they would lose literally dozens of pounds of body weight on the long swim, mostly glycogen reserves, fat, water and protein. Which meant that in addition to priming themselves with improbably hearty breakfasts, they should pause often enough along the way to replenish their depleting bodies.

Which was not easily done, they learned on the early practice runs. If there was any chop on the water, sandwiches were almost impossible to keep dry. Whole fruit – apples or pears — proved hard to bite and chew, and dried fruit was hard to swallow. The pasta salad some recommended for its carbohydrate boost was hopelessly difficult to eat while treading water.

In the end they invented what later generations would call smoothies, thick with fruit and pulverized nuts and peanut butter but thin enough to be swallowed down. They then learned to have at the ready, as chasers, guzzle bottles of water – or better, diluted fruit juice — with a pinch of salt.

There were licensed pilots and rules, they learned – the Channel Swimming and Piloting Federation, whose members were a formidable and expensive guild insisting that swims be closely monitored by experts. But it proved not hard to rent a suitable sturdy boat that they could pilot themselves for practice swims of growing distance. And then who would know if one fine day they went all the way across?

And so they did.

They drew straws to determine the order of play. Charles went first, on a lovely late August day with negligible wind or waves. He made it across in 12 hours and 55 minutes, which was better than the posted averages. They bundled him in blankets and laid him out on a bunk while Howard steered the boat back to the foot of the white cliffs, Lisette reviving her husband with sips of hot soup.

They made it back in time for a decent night’s sleep at the dockside hotel from which they’d started. Next morning the weather was even better, and Howard felt fresh enough to take his turn. Somewhat to his astonishment – Charles being younger and presumably more fit — he made it in 12 hours and 22 minutes, a bit more than a half hour’s advantage.

Howard offered to credit the weather for his win, and forego the prize. Charles, though, would not hear of it. After a few days’ rest and recuperation in London, the four of them took a proper boat and train to Paris. Charles made good as host for a long weekend of art museums, opera, theater and dining that none of them would forget — especially since it turned out to be their last time together.

Almost as soon as they were back in London, Charles was offered the post he had long dreamed of, at The Louvre. Within a few weeks he and Lisette were gone.

They stayed in touch nonetheless, more than just birthday gifts and holiday cards but, as best friends might expect of one another, phone calls as well, and then Skype calls. As the smartphone revolution took hold, they called each other several times a month, more often than not Facetime calls, sharing trials and triumphs and on the tiny screens watching each other mature and then begin to age.

Not only did both men revel in the careers they had crossed the Atlantic to pursue; both wives took on advanced academic work and had careers of their own, so their conversations were rich with discoveries. Neither couple had children, which they confessed — to each other but not to others — was a choice, not a personal tragedy.

Their childlessness should have made long weekends or summer vacations together natural, re-living the peregrinations of their first years. But although constantly promising to visit each other, they somehow never managed any sort of reunion. The years passed.

And then Lisette fell ill. It was clear almost from the start that she would not last: It was cancer of the pancreas, which the whole world understood would surely be terminal unless caught very early, which hers was not.

Meg thought she and Howard should take a long weekend to visit their stricken friend, to be at her bedside in the villa in Nanterre outside Paris that would seem familiar because of photos Charles had sent.

They might cheer her up, Meg thought, with scrapbooks of pictures and maps, menus and advertisement flyers of their early adventures. If that proved unsuccessful or inappropriate, she said, they might at least pray with her, poor Lisette, calling on a God none of them truly believed in to lift her spirits, or lessen her pain and her burden, or — at the very least, or most — to shorten her agony and her life.

But the two of them somehow never managed to free themselves of their academic duties at the same time to undertake such a mission. Before long it was too late, poor Lisette being so diminished and unaware of those around her, Charles reported in his increasingly frequent phone call, to appreciate or even recognize strangers from her earlier life.

Dear Meg was not deterred. Howard, who had taken his parents’ early deaths as unhappy omens of his own vulnerability, had no stomach for sitting at the bedside of the dying. So she went alone, and said in her first phone call that Lisette recognized her even before she spoke, which brought tears to both Meg’s and Charles’ eyes. Lisette rallied, his wife reported, and was so uplifted that she managed a cup of consommé and a brie de Meaux with craquelins aux herbes that Meg had found in a fromagerie close to where her train had arrived at the Gare du Nord.

That initial afternoon’s visit, on a glorious April day, was so successful that Charles implored her to stay a day or two longer, thinking that the stimulus of a beloved old friend might be the elixir that would help his Lisette overcome the disease, amaze the doctors and revive to a long life. So Meg reported to Howard in her nightly phone calls.

It was a remarkably big villa, she said, with a small but loyal staff of maids and cooks, and of course round-the-clock nurses for Lisette. She had a guest room of her own, to which she could repair for a nap when her continued presence seemed to become a burden for the poor patient. And then after another bedside visit she could spend some time consoling poor Charles over an excellent dinner and a glass of Armagnac, a brandy that the French call a digestif.

Her ministrations to Lisette, whom she visited at least twice a day, seemed initially so successful that she stayed almost a week. As the days wore on, though, Meg reported in her dutiful calls, it became evident that the healing effect of her visits was fading. Lisette would not after all have a miraculous recovery — but might nonetheless linger on for weeks or perhaps months.

So Meg at last came home to a husband who had longed for her embrace, and assured him that she had missed him at least as much as he yearned for her – as she demonstrated after a few night’s early sleep to recuperate from the memory of their friend’s pain.

Lisette did in fact last another two months. When the end came, Howard and Meg had a long, consoling Facetime conversation with poor Charles. They would have come to the memorial service and interment, they explained, but Meg had borrowed so much time from her work, in order to visit Lisette in April, that she could not now break away again. And Howard’s discomfort with death would not allow him to come without his wife to succor his spirits.

So poor Charles laid his wife to rest without the sustaining presence of his best friends.

* * *

And then Charles came to them.

It was a glorious July, the weather balmy but not sticky-hot as it can be in the English summer. He phoned first, a Facetime call so Howard could see that he was a bit gaunt, perhaps not yet recovered from Lisette’s passing. Meg, who had seen him only a few months earlier, thought he hadn’t been eating well, and needed only a few ice cream cornets.

He was lonely, he said, and depressed; could he come for a visit?

Of course! They both said into the smartphone. Howard turned it sideways – landscape, he was supposed to call it – to be sure Charles could see them both beaming at him. How soon could he come?

“How about tomorrow?”

“Perfect!” they said almost in unison.

“Where will you land?” Meg wanted to know. “Heathrow is closest, but I could meet you at Gatwick or Luton or even London City.” She had the week off. Howard, unhappily, had signed up to teach a very well-subscribed summer course, so was less flexible.

“I’ll try to book into Heathrow,” Charles said. “Let me call you back in a few minutes.” And just like that he was gone.

But not for long: They had hardly begun buzzing about what to do with him – Meg wanted to do the Cotswold Hills inns again – when he was back on the smartphone.

“Done. I’ll land at Heathrow Terminal 2 at 11:13 in the morning. Don’t you bother coming into the airport; there must be a place where passengers can meet drivers.”

“There is,” Meg said. “We had a friend from the U.S. recently. You ask to be directed to the Short Stay Car Park, Level 4. Phone me when you’re there; I’ll be only a few minutes away.”

“Short Stay, Level 4. Je comprends. I have it. I suppose it will be noon by the time I clear customs and get there. I’ll keep you posted by phone. This same number?”

“No, this is Howard’s. But come to think of it, you obviously have his number in your system, and his is newer and better. I’ll bring this phone and leave mine with him. See you tomorrow!”

Which was how Howard ended up taking Meg’s phone to class with him the next day. Thinking that he might phone Charles to say ‘Welcome home’ if there were a timely moment between classes, he looked to see if Meg had him in her contacts. Of course! She’d spent that week with them before Lisette’s passing. It looked as though perhaps she’d phoned him not too long ago, but he wasn’t good with these gadgets and it hardly mattered, so he gave it up and went back to teaching.

The airport pickup went as planned, and they were in the parlor with glasses of sherry when he got home in late afternoon. Charles insisted on taking them out to a really good restaurant, and Meg phoned Sabor for a reservation. It turned out to be a wonderful evening, remembering all the places they’d visited together back when they were, as Charles put it, the quatuor fabuleux, the fabulous foursome.

They sat up late on getting home that night. Howard, knowing he had to teach in the morning, tried to nurse the French brandy Charles had brought. He thought of turning in alone, leaving Meg to carry on as hostess, but his mind turned to the calls he thought he’d seen on her smartphone, and he stayed up until it was appropriate to suggest that they all call it a night.

He had breakfast alone the next morning – Meg needed to sleep off a brandy-induced buzz, and his first class met at 9 – but he left a note promising to join them for lunch.

That, as it turned out, didn’t happen. Meg texted him that she’d done some research, and there was a matinee performance – A Comedy of Errors – at Stratford-upon-Avon, which was less than two hours up the M40 motorway, and they were off.

As luck had it, Howard had silenced his phone to teach his class, so was unaware of the text. He hurried home – even being rather short with a few students who wanted a word with him – only to find an empty house. After calling their names and poking about the house and garden, he took out his phone to call Meg, and only then found the text and realized he would lunch alone.

He briefly considered jumping in his car and motoring up to join them; he could probably have just made it before the play began, and the Royal Shakespeare Theatre would not likely be sold out for a midweek matinee. But he might not be able to find a seat near them, and then they would have to drive back in two cars, which would make no sense. He went to the fridge to rustle up something for a lonely lunch.

Just as he’d decided on the lobster salad that Meg had made before Charles invited them out for dinner last night, it occurred to him he might get an Uber ride to Stratford. He had shut the fridge door and taken out his phone, about to summon that app, when he realized that Meg and Charles had gone in her little red Porsche Boxster, a two-seater, so he would end up taking an Uber back, which would serve absolutely no purpose.

The very least he could do was wish them well, so he phoned Meg. She was appropriately apologetic. She’d hoped he might notice the text and get back to her this morning, she said, in time to arrange making the outing as a threesome. But when she didn’t hear from him she’d decided to do Shakespeare anyway, for old time’s sake, and had left him a note which perhaps he’d found on the refrigerator door explaining their absence and urging him to make a lunch of anything but the lobster salad.

They’d had a lovely lunch at the classic Lambs Restaurant, she said, and Charles was just settling up; they needed to get to the theater so she’d have to ring off. Understood, he said, but unfortunately he’d missed her note and had already lunched on a bit of the lobster, but perhaps there was enough left for a light supper and anyway enjoy the show.

He pocketed his phone and went back to the fridge, gave himself a generous helping of lobster salad, poured an equally generous glass of a middling pinot grigio, and after a time retired for a long nap that made up for his early rising. Although the shortest of Shakespeare’s plays, Comedy of Errors would not close before 4, and rush hour traffic on the motorway would keep them until close to dusk, perhaps 6:30. He went to his study to prepare his next several classes.

He had just settled down in the garden with a glass of the pinot grigio when they arrived. Meg went to the kitchen to get glasses for the two of them, and Charles fairly jumped at the chance to have a few minutes with him alone.

“Are you still swimming, Howard, mon ami?”

Howard was feeling good enough to resurrect his rusty French. “Mais oui, absolument! I work out at a gym with an Olympic-size pool. I do a fairly conventional exercise class, and then I hit the pool, 800 meters minimum. And you?”

“Malheureusement, I didn’t do much during Lisette’s illness. I was spending time with her, of course, but that was just an excuse, because she had plenty of help. A vrai dire, I was too depressed. How do you say Je me laisse perdre la discipline ? I let myself go ?

“You must have gotten back to it; you look hard enough now.”

“C’est vrai, I’m working on it. But if we played The Channel game today, you’d beat me again.”

“I think not, Charles. You spot me, what, five or six years? You’d have the edge.”

“But it would be fun, ¿non? What do you think? Make a game again of what we French call La Manche?”

“Swim The Channel again? Charles, my friend, I’m not sure I could make it. Not sure either of us could. Neither of us has been training.”

“We could change the rules of the game. Make it whoever gets farthest.”

“What, the first one plants a stake in the ocean wherever he gives up and climbs into the boat?”

“Ne sois pas si démodé! Don’t be so yesterday. We all have GPS on our smartphones; we can mark that spot avec précision, mon ami.”

Meg, when she rejoined them and caught up with the conversation, professed to think they were crazy. “Neither of you can swim that far without a month of training. What kind of game is it that assumes giving up halfway?”

But the more Charles talked about it, the more she seemed to relent. It would be fun to learn the GPS app and mark how far each of them got. But how about health? Howard had recently seen his cardiologist, who declared him, with a wry grin, “sound as a dollar.” Was Charles sure he was proof against a heart attack?”

“Bien sûr! I had a thorough checkup after the funeral. I’m prêt à partir – how do we say it in English? — good to go.”

Well and good, Meg said, they might postpone a decision on that foolishness, but meantime she’d discovered that Howard has eaten more of the lobster salad than he’d let on, so they should talk about what else she might concoct for supper. Charles suggested that the Aquavit, with a famous smorgasbord, would be ideal for people who’d eaten well at noon, so off they went – and spent most of that meal talking about La Manche.

By the time they finished the brandy that evening, it was decided. The weather forecast was perfect; they’d found an app assuring them that The Channel water was warmer than it had been two decades ago. They would play the game again; Howard would go first this time.

He had second thoughts the morning they started out. But it would have been unsportsmanlike to renege at the last minute.

“Do or die!” he said as he plunged into the English Channel and struck out for France.

End-

This is very clever! Thanks for sharing.