Published in the Canadian Literary Heist in December 2016

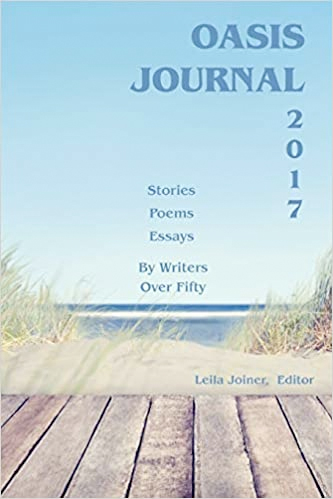

Reprinted in Oasis Journal in September 2017

He felt in his pocket for the key. The place belonged to the bank or the auctioneer now, but they would hardly mind his coming for a last look around. By the end of the day there might be nothing left but the empty walls with which he’d started four decades ago. Rudy’s Hardware, in old-fashioned huge neon script, stood out in the infant dawn.

Good: They’d had the decency to leave the sign switched on. In the plate-glass window, his tall, lanky reflection had a ruby cast that gave way, as he neared the door, to the pallor of the overnight lights inside.

He smiled at himself under his wide-brimmed canvas bush hat, the trademark image he’d adopted on his first day of business. Taking a deep breath to expand his chest, he gave himself a toothy grin, then deftly opened the door, strode to the counter and reached over to disarm the alarm system and turn up the lights. He didn’t want the beat cop seeing a dim mysterious figure in here; better to be easily recognized as good old Rudy.

The shelves and wall displays were pock-marked with empty spaces, evidence of his reasonably successful going-out-of-business sale. Today someone – maybe from a nearby town, an entrepreneur still trying to stay in business against big-box competition – would buy for a song whatever was left. He didn’t expect Lowe’s or Home Depot to bother coming: They bought by the boxcar, and would have no interest in archaic stuff like the half-full kegs of nails in the back room.

Forty years ago, he’d hoped for an heir who might carry on this business. Now he was glad not to bequeath anyone an albatross; just as well that Myrtle had proved unproductive. In their courtship, she talked about wanting a family but, once wed, was not inclined to spend much time or effort trying to start one. He finally went alone to be sure his sperm count was adequate; she declined to be tested. She came to the store for the grand opening, but never again; she became a tolerable cook and a prize-winning bridge player. Her death twelve years ago was a bearable loss, and he’d immersed himself still further in running the company.

Forty years ago, he’d hoped for an heir who might carry on this business. Now he was glad not to bequeath anyone an albatross; just as well that Myrtle had proved unproductive. In their courtship, she talked about wanting a family but, once wed, was not inclined to spend much time or effort trying to start one. He finally went alone to be sure his sperm count was adequate; she declined to be tested. She came to the store for the grand opening, but never again; she became a tolerable cook and a prize-winning bridge player. Her death twelve years ago was a bearable loss, and he’d immersed himself still further in running the company.

His meandering had taken him now into the back room, where a sagging upholstered armchair squatted among the shipping boxes. There had once been a second-hand sofa squeezed into that spot. If Myrtle had ever come back, he thought, she would have disapproved. He took the view that his floor clerks might occasionally stay alert by taking quick naps.

A real hardware man needed an encyclopedic memory, an intuitive grasp that the thingamajig a customer described was a number ten left-handed screw — and the unhesitating ability to find it on the store’s shelves. With one exception, Rudy hired only such men – and they’d been increasingly hard to find. Walter had been with him from the start, persuaded to stay on long past 65; Oscar and Howie – “the boys” — were almost as long in the tooth. He’d given all three and their wives first-class tickets to Florida as retirement gifts, and they were off into promising sunset years.

They deserved it: Customers had come from miles away to benefit from their expertise. Of course, in the latter years that became his undoing: People came to buy left-handed screws for a few dimes, but went to a superstore to buy their hundred-dollar power tools.

The exception to his male staff was the girl behind the counter. From the beginning, Rudy knew that men – until a few years ago, customers were overwhelmingly men – would appreciate a shapely girl with a pretty face and a warm smile as they opened their wallets.

Peggy McGuire was the first, an Irish colleen who met all of his criteria, including shoulder-length black locks with just a bit of curl – and smart, besides. In hiring her, he did not intend anything more than casual male appreciation of female pulchritude.

But a young man whose wife is more interested in bridge than bed is vulnerable to impulse. Peggy stayed after closing one night to help him take inventory. She responded with apparent enthusiasm to his tentative kiss. As their lip-locked fondling and fumbling grew more passionate, he thought briefly of finding some place more comfortable, but his ardor would brook no delay; she was eagerly compliant when they ended on the sofa.

He needed to invent no story when he got home late: Myrtle was still at a bridge tournament. He fell into a sleep adorned with unaccustomed dreams, and was only dimly aware of his wife’s return. Next morning he slipped away early, determined to call his lawyer, manage as painless a divorce as possible, and make an honest woman of Peggy McGuire.

She did not come to work.

He telephoned, but got no answer. He manned the checkout counter himself until lunchtime, when he deputized Walter so that he could go to the rooming-house address she’d given in her job application.

His knocking on her door yielded no response from the apartment but roused the landlady. She had paid off her rent and left this very morning, the woman said. No, she had left no forwarding address.

He remembered the night before as a mutually innocent, spontaneous coupling, but she must have recalled an inappropriate initiative of a predatory employer. He stopped at the newspaper to place a want ad for a new counter girl, and went back to the store despondent.

There were many handsome young women over the ensuing years, but he never again let one stay after hours. Over protests from Walter and the boys, he replaced the guilty sofa with the armchair, smaller but still serviceable for short naps.

Walking back into the main store, he surveyed the counters and shelves. Here were toilet flush valves: an originally simple, workaday mechanism that a dozen or so inventors had tried to improve. A good hardware store had to carry them all. Door knobs: a dozen here, from brass to chrome, round to levered, and an even wider assortment of strike plates. Garden hose washers in rubber, vinyl, plastic, all in several sizes. Light switches: How many ways were there to turn power on and off? He counted: seventeen. And three shelves of light bulb sockets, extension cords, three-way adapters, incandescent bulbs, fluorescent tubes, the new LEDs. Not to mention any nut, bolt, washer or clevis pin anyone could possibly want. People snapping up final-sale bargains had picked it all over, but there was a lot still left.

He sighed. Let someone else keep track of all this junk; being shut of it would be a relief. But unlike Walter and the boys, he would retire to no domestic bliss; he’d have to take up golf or woodcarving or even for God’s sake cards – poker, maybe, not bridge — to fill the empty hours that yawned ahead.

The day had brightened; there was busy sidewalk traffic. He should turn out the lights and go down the street to the donut shop to kill time until the auctioneer would arrive.

But there was a man outside, rapping at the door. A younger fellow, tall, rangy, dressed in denim jeans and jacket. For a moment he thought it a reflection, but the renewed rapping assured him it was a real live man, and obviously not someone from the bank or auction house. He pantomimed refusal, holding up his arm to point at his watch, shaking his head no.

The stranger knocked again, pointing that he wanted to come in.

“Not until ten!” Rudy shouted through the glass.

“Not a buyer!” the fellow shouted back. He held a hand to his brow, miming. “Just want see to the place before it’s gone!”

Intrigued, Rudy let him in. “Tell me again,” he said in a normal voice, “what is it that brings you? You’re not here for the auction?”

“No, sorry. I promised my mother I’d come have a look before your famous hardware store became an empty shell.” He took a smartphone from his pocket. “Do you mind if I take a few pictures for her?”

“Help yourself.”

“Thank you. He began snapping away.

“Who did you say these were for?”

“My mother. She read in the paper that you were going out of business. Would you mind standing over here for a moment? The light will be better, and I can get you in a few photos.”

“In the early days, my customers were all men.”

“Yes. A lot of housewives nowadays can make repairs as well as their husbands, but Mom was a pioneer.”

“Her husband didn’t mind? There are men who feel challenged. Manhood impugned, you know?”

“Mom didn’t have that problem. She was a single mother.”

“I’m sorry to be nosy, but how old were you when they divorced?”

“I guess I’ve intruded, so you have a right to be nosy. I never knew my father. Could you maybe take off that hat for a minute?”

“Why, sure.”

“It shades your face, you know? She’ll want to see how you look nowadays.”

“Pity you didn’t bring her. I’m in kind of a nostalgic mood, and it would be fun to see someone from the earlier days. How far away is she?”

“Not all that far. Unionville. Maybe a half-hour. But she’s not very mobile nowadays. In an assisted-living place, you know? Sound of mind, but a bit frail.”

“That’s too bad. How long ago was it you said she shopped here?”

“No, not shopped. Worked. She said you hired her not long after you opened the store.”

“I’m sorry, did you tell me your name?”

“Apologies, I should have.” He put the smartphone in his pocket and held out a hand. “I’m Rood.”

“Rude? Like impolite?” He took the offered hand for a tentative shake.

“No. R-O-O-D. One of a kind, I think. She’s never told me where she came up with my name.”

“Rood . . . .”

“Sorry. Rood McGuire. I work for the bank down the street. Farthest thing in the world from a hardware man. She told me about hardware men.”

“Yes, a special breed. She would remember. Unionville, you said?”

“Yes.”

“I wonder if she’d be up to a visit? Maybe you could give me the address.”

-End-